Leos Carax interview re Holy Motors

Carax has always stood deliberately apart, with his cigarette and sunglasses, as a lone voice seeking the ineffably romantic in cinema. A wave of teenage cinephilia flowed into his first two features – Boy Meets Girl (1984) and Mauvaise sang (1986), but their evocations of the New Wave were joyful rather than derivative, the cool look worlds apart from the cool look of contemporaries Luc Besson and Jean-Jacques Beineix. Les Amants du Pont Neuf (1991) was as grand a romantic gesture as could be, to Juliette Binoche, to Paris, to love. The personal and artistic torment of Pola X (1999) had it dismissed in some quarters as wonky at best; it now looks like one of the best films of the 1990s.

The boy-meets-girl theme bubbles under even in Pola X, but with Holy Motors Carax takes his eye from the petri dish of a relationship, to cast it as broadly as possible. Gone is the exhilaration of love but, with something of the spirit of Jean Cocteau and Georges Franju, there is a deep, nostalgic emotion running through the film, which has its own sweetness, encapsulated in the protagonist’s answer to why he continues: “pour la beauté du geste.”

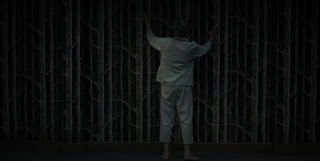

The film follows M. Oscar (Denis Lavant) through a series of appointments in which he assumes a different role, from silver-haired businessman to old beggar-woman, and on. Part of the film’s project is a hymn to the actor, who lives so many experiences on our behalf. Another part is to recognize that this capability exists in us all, and that the sense of identity is fixed far less than we should assume. It’s the classic Man Without Qualities existential dilemma, and no wonder Oscar takes to the late-night bottle in the back of his stretch limo, desperate for some human contact.

As Carax put it when we met (AFI Festival 2013), Holy Motors “was born from the rage of not being able to make films for so long, so it was imagined very fast and shot very fast, without watching the dailies. It happens in one day, from dawn to moonlight. It gave me the possibility to show in one day a whole range of human experience. Of course there is a game with virtuality in the film, which we know about more and more, because when you talk about reality, one of the questions is, can we avoid it? Some people try through fame, or money, or entertainment, or these virtual worlds. What happens if more and more of us try to avoid it more and more? We’ll see.

“I’m not a cinephile, but people, critics, tend to see my films in terms of cinephilia. The language is cinema, I hope, but I don’t see Holy Motors as a film about cinema. People ask what is it about, and I say I don’t know, because I don’t really understand the word “about”. Is Hitchcock’s The Birds about birds? Films are metaphors, and in this case I tried to invent a science-fiction world, because science-fiction is great for that – it’s a metaphor for reality. So hopefully the film is about that, about the structure of reality: can we still face it, do we still want lived experiences, do we still want action? Action means responsibility, and this kind of science-fiction world that was invented for the film, with this strange job where you travel from life to life, I felt it was a good way to show the experience of being alive. He doesn’t have any present. He doesn’t have what people call a life, or at least you wonder if he does, or what is his life. In my mind it’s different movements inside any life, inside many lives, dealing with what we all deal with, which is ageing, dying, loving, losing etc. It’s a strange pitch for a film – what is your film about? It’s about the experience of being alive today.

“I started making films quite young, and I stopped making films quite young. I made three films from 20 to 30 years old, and then I couldn’t make films again until I was 38. And then again ten years. So I had a life within cinema, but I can hardly call myself a filmmaker. Probably in this film there is something like a jump, where suddenly I wake up and I’m not 20, I’m not 30 anymore, and this question of who am I becomes important.

“I changed my name when I was 13 years old. I wasn’t yet interested in cinema at that time. I don’t remember exactly who that boy was at 13 years old, who I was, but I guess I felt the need to reinvent myself. I think every child should be allowed to change his name. You should be allowed to say at 12 or 13, you had your father’s name for a while, or your mother’s name or whatever, now it’s your turn to invent your name and write your life. I have six nephews from aged 10 to 25, and sometimes I worry that they don’t see that, that it’s possible to write your life. Of course, you can’t write all of it, but you can try. It relates to what I was saying about experience – do we still want experience? I’m not against virtual worlds or connecting through computers or whatever. Connecting is the opposite of fighting, of resisting. All these possibilities that this virtuality offers are wonderful, and I hope I used them in Holy Motors, but as a lifestyle I don’t like it. I’m worried about the fact that young people are maybe not searching for experience so much anymore. Which always existed before: young men wanted to go to war, or take boats. They wanted to reinvent themselves. Whether young people still want that I don’t know.”

The fact that Holy Motors starts with Carax himself, waking in bed and passing through a magical portal into a cinema auditorium, has naturally enough prompted assumptions that this is a film about cinema. This is true only to the extent that it is about what cinema can show us of ourselves. There are few specific references, save Carax letting his hair down at the end, along with Edith Scob (as Oscar’s driver ), as though he had been restraining himself. The film cameras, he laments, are one part of a change, a shrinking from reality, that the talking limousine makes clear at the end with a call for silence: “men don’t want visible machines anymore.” It is a film not about cinema, but born of cinema. Carax’s Island of Cinema is a place we recognize. It is not a place of reference, or stealing, but a place for looking at ourselves in different ways. Thus the shadows of genre in Holy Motors, and the feel that when the camera swoops up to Kylie on a balcony, wailing a lament (by Neil Hannon) in the abandoned deco shopping mall that itself figured prominently in Les amants du Pont Neuf, this is some gushing musical in the Demy tradition. But it is not: the song is rather lovely and apt, the moment is perfectly judged, and this is a particularly potent way of conveying the emotion of nostalgia, as she sings “who were we?” The evocation here, as elsewhere, is less referential of cinema of the past than a rather convincing impression that they don’t make ’em like that anymore.

“It’s usual when people talk about my films that they don’t give the desire to people to go and see them because people think, oh it’s a film for specialists, it’s a film for cinephiles. This I mind. I’ve shown the film to 13-year old kids and they get it. They don’t know anything about my cinema, about cinema in general. When I started making films I used references a bit like the New Wave did, to be playful, to be fun, to say I love cinema, I love films, I love film history, but I stopped that after my second film. I felt I had paid my debt to my love for cinema. That’s why I don’t call them references any more. It was nothing very conscious. There were two conscious things. One was that Denis Lavant was going to run on the treadmill and re-enact in a way the scene from my second film, in the virtual world, but it doesn’t change anything if you haven’t seen Mauvaise sang. You still get it. And then at the end of the shoot, I decided to give Edith Scob the mask close to what she had in her earlier film when she was 20 [Les yeux sans visage, 1960]. I hesitated, but it felt absolutely right, and like a gift to her, because I loved her so much on the shoot and I think she loved the experience of the film. It was like a present, and I felt it went with the film, that she should put a mask on at the end. But it was not to say hello to the Franju. I don’t think in those terms, but of course I’ve read books and I’ve seen things and they appear in my films, for sure.

“It may be strange, but I see cinema as more than films. Obviously I loved films, and I’ve seen many films, when I was younger. When I call it an island, it’s because it’s a place, a place where you can see these things – life and death – from a different angle. So I’m grateful that I can go back to this island, but I don’t need to see films to love cinema. I’ve never seen my own films again. You have to fight so much. Making a film is one way of trying to stop the fight and trying to look, to see. That’s what I like about cinema.

“Sometimes I think I should see more films, especially when I travel, but then I see one or two that discourage me. When I was younger I didn’t mind seeing bad films at all. To see a bad film could be very inspiring to me. Now it’s not the case; it’s depressing. I don’t have the courage of discovering that I used to. Now I watch films because I want to see an actress in a film, or the work of a DP. Last year I saw a film I thought was good – it’s not a great film, but it does try to show something of the superhero discovering his powers – Chronicle (2012). It’s a small film, about three kids who discover they have super powers; a cheap film, for sure, compared to usual superhero films, but when they have the scene in the sky where they fly, it’s not like two shots that costs millions of dollars, it’s a long scene and they fly. It’s nice to see people in the sky flying, simply. I am always surprised when you see that kind of superhero that they don’t use that. He lands and it’s over. Flying is great – if a man can fly, keep him going for 20 minutes flying, go around the clouds. This film has a bit of that simple strength. If someone made a film where someone would fly for an hour and a half, people would go see it.

“Movies started with motion, motion pictures. That’s why I showed these images from [Étienne-Jules] Marey, these 19th-century images. It’s the human body – we still love to watch the human body. We love to watch other things, landscapes or things we invented, the cigarettes, the guns, the cars, but basically what we all love is to watch a face, or a human body in motion, running, fucking, exploding. This is what motion capture is. You still need the holy motor of a human body to create it, and in that sense it’s exciting.

“My films are not always light, but with each film I’ve felt the need to try to reach joy, through speed, through dance, through music. In this film I tried through the intermission scene with the accordions, because I think joy is important. I don’t know much about happiness but I know I need joy.

“Each film has really felt like the first one and the last one. I feel like an imposter in a way because I didn’t study film. I was never on a shoot before I made my first film. The fact is that to make a film you need people, and I’ve had lots of trouble to find people. It’s not so much the money. I don’t think I’ve ever not made a film because of money. It’s always people; whether it’s not finding an actress, a producer, someone I trust, it’s people. The hard thing with cinema is people. The other reason I haven’t made many films, apart from all the problems, is probably that once you make a new film, all the past projects are dead. When I make a new film I have to feel that I’m not the same person as the one who made the film before.

“Albert Prévost is the one who made Holy Motors possible. We met on Lovers on the Bridge. Money is very abstract in cinema. You can have, let’s say, $1,000,000, which is nothing to certain producers, and worth a lot to other producers. This man had a kind of genius that I think is pretty rare. It worked for me, but it doesn’t mean it would work with any film-maker. To know how to make a dollar into $10, or when I wanted something, really he understood that that was important for the film, that some money had to go there. And he was able to transmit that to the crew. People trusted him. They knew that he wasn’t spending money behind their backs. When I started making films, I always worked with people who were like crooks, but good crooks. Well, not always good, but the ones I liked were good. To be a producer of a film you have to have a kind of craziness. I think it’s always been true with cinema, and that makes it kind of exciting. The first big producers, in the silent days, were crazy. They were capitalists, they loved money, but they were crazy. If you don’t have that craziness you make bad films, or you make boring films, or you just don’t make films, and I think it’s really that craziness that we miss. It’s rare to find. Cinema from the beginning was something crazy. It’s the only art that’s been invented. Other arts didn’t need to be invented. It’s a miracle it exists.”

As one might expect, Carax is a lover of celluloid, but embraces digital technology in Holy Motors both to rejoice in the movement of the human body in the motion-capture studio, and to create degenerating, subjective visions of Paris as Oscar gazes from his womb-like limo.

“Everything has changed with digital. When I was 20, I met the DP I was to work with for ten years, [Jean-Yves Escoffier], and he became my best friend, like a brother. Then after Lovers on the Bridge, we didn’t talk for ten years. He moved to Hollywood, and he died out here. After that, working with light, working on celluloid, was not the same for me with other people. That was one thing that helped me go to digital because I felt that if I don’t have that kind of relationship with a DP, I might as well shoot digitally.

“I have a bad reaction to digital, mainly because it’s been imposed on us, and I hate that. It’s been an issue since the beginning. Cinema was a very powerful invention, but obviously this power of cinema – it’s like a holy power – you have to reinvent it all the time. Nobody’s scared of seeing a train coming into a station any more. So every generation has to reinvent cinema, the power of cinema. If you see a man walking in an F.W. Murnau film, and the camera is following him, you feel like he is being watched by a god. If a kid does the same shot today and shows it on YouTube, you don’t have this feeling at all. So cinema has to reinvent its power all the time, and that’s what I feel has to be done nowadays more than ever, to reinvent the power of cinema, because if not, it’s lost, it’s not there. People think it’s still there, because they’re entertained by cinema still, but truly if it’s not reinvented, it’s stale. The power has also been devalued by images – images are not only in cinema today, they’re all over the place. You go in the streets and there are screens all over the place, images all over the place. To reinvent the experience of watching something is getting harder and harder. It always seems strange to me that most films are only references, like a photocopy of each other. Hopefully I’m trying to invent something.”

Holy Motors was greeted at Cannes with surprise, as a new sort of thing, and a bolt from the blue. It is a new sort of thing, but it’s also an old sort of thing. The opening specifically evokes Cocteau and a brand of poeticism that is not seen so much any more, perhaps because the idea of a grand aesthetic gesture, the aiming for something greater than literal truth, is not so much in fashion these days. It is a unique, personal gesture. One of the finest things about Holy Motors is that it does not feel definitive. Tomorrow will be completely different, as it should be.